The Credit Crunch and recession is like a great sea-battle. All banks like the great galleons at The Battle of Trafalgar have been damaged, some boarded and taken for prize money, some broken up and sunk, and all variously crippled having to try to return to port in the one of the greatest storms of the century, just like the enormous storm that battered all survivors after Trafalgar in 1805, victors and defeated alike. The Credit Crunch and recession has become a competitive battle between countries to see who can look least damaged and take the prize money thanks to the sovereign debt crisis, which as the last G20 meeting showed has this year severely weakened the collective spirit of G20 that we are all in this together and must cooperate to solve what is a global not a national problem.

The new message is that it is every country for itself, and this changes the use and meaning of stress tests by the banks. What looked like a climatic disaster for the global economy is now turning into a battle between countries. Germany defeated Greece and the PIIGS in the Euro Area, but the Euro Area is now at economic banking war with the Anglo-Saxons, USA and UK, within the EU and transatlantic. At stake may be the coming recession for the Euro Area and how deep and prolonged this will be. But, I know that there will not be a comparable or even roughly precisely similar modeling of the stress test scenarios by all banks; they will each be as different as the pictures shown here of the battle of Trafalgar, partial, subjective, and incomplete.

Public transparent stress tests in the middle of the sovereign debt crisis concern risks whether the Euro Area can hold together as well or better than the G20 agenda, or whether the Euro Area splits between externally strong and externally weak states, surplus and deficit countries, competitive and less competitive.

These are the analyses of banks in each national sector that we experts will be examining. The Euro Area does not seem to have recognised and decided openly that sharing a common currency means they are mutually dependent. There remain strong political voices advocating the break-up of the Euro Area, letting some sink so that others can survive. Sensible people know that way lies defeat for all. Euro Area divided will lose and set back for another generation Europe's dream of action as a counterweight of equal strength in the world to the Anglo-Saxon economies who do operate as a group even though not formally so. Greece, Spain and Ireland thought Euro membership protected them; it hasn't. Germany and other export-led economies, including far-flung China, think they are protected by their trade surpluses, and have yet to discover fully that is not so either!

Stress tests by banks are like war gaming, and at least as complex as a sea battle between two gigantic fleets. They are a regular requirement dictated by law, by Europe's CRD (Basel II and Solvency II) legislation adopted by each EU member state. the "stress tests" are central to Pillar II of Basel II.

Arguably, the Credit Crunch was worse than it would have been if only the major banks in Europe had focused earlier on Pillar II and completed Pillar II before the crisis; none of them did so! They had been advised strongly by audit firms (insofar as they said clearly banks must begin by building up their historical data including data covering at least one earlier recession) and consultancies like myself to start with Pillar II back in 2005 and not to wait until Pillar I implementations were complete; none did so!

It is debatable if the regulators communicated the same signals. I don't think they did even though intelligent regulators knew long ago that Pillar I of Basel II was really only a temporary learning process and that Pillar II is the entire battleground of risk regulations. They knew this at least by 2007 when it was obvious banks were dragging their anchor chains on Pillar II work, if not earlier, including about the inter working required with IFRS accounting standards that also reflect the scenario modeling requirements of Pillar II stress tests etc.

What is Pillar II?

What is Pillar II?It is not merely the supervisory pillar as the audit firms wrongly advised by simplifying or summarising the meaning of Pillar II. Pillar II requires firms to combine all their risk exposures into a set of macro models with scenarios based on cyclical changes in the underlying economies. Essentially it is all about getting banks to understand how their performance depends on the macro-economy. Unfortunately this was not a message they either understood or wanted to hear. Bankers are deeply suspicious of power grabs in the boardroom by economists 9who would then displace mere accountants and mathematicians) despite the latter showing no signs whatsoever of being hungry for such responsibility. Economists were not involved by banks in their efforts to build econometric models for scenario stress testing. The regulators required them to forecast using current risk accounting data in the context of a range of severe economic downturn factors. Bankers assumed this could be done by simply tweaking their risk accounts and the result universally was amateur hour quality. You can see it in the results and also in the recipe provided of headline numbers the banks were tasked to work with, not unlike battles led by generals who had never seen a war, didn't know what a whole fleet or army even looks and behaves like. Banking had not only become too complex for traditional regulations but also too complex for management, for new management that unlike traditional predecessors had less than a comprehensive understanding of basic banking.

Then in 2008 and 2009 along came just such a crisis, full-on war of survival, survival of those banks who could look at least relatively better than others, and as they had avoided modelling full recession, but also Credit Crunch, which effectively more than doubled the losses that they should have had calculations in place to anticipate. If they had been more on their own case I calculate their capital buffers and reserves would have been half as much again, but this would only have ameliorated half of the Credit Crunch impacts. Governments would still have had to step in. But, in any case, only the US and UK met the crisis with sufficient financial muscle and innovation. There was little prospect of banks surviving unaided unless regulators were more on the ball about systemic risk already by 2006 at the latest, but in every country that was less the remit of regulators, more the responsibility of central banks, who weren't asleep at the tiller on the poop deck and in the conning tower so much as merely lacking a sense of urgency to get anywhere fast. They relied too much on visual sightings from the crow's nest, lacked a plan and lacked modern guidance systems to see over the horizon.

G20 and Government ordered stress tests on both sides of The Atlantic in 2009

G20 and Government ordered stress tests on both sides of The Atlantic in 2009With the Credit Crunch and resulting recession suddenly stress tests were no longer about speculating about an indeterminate time in the future, but about what is happening all around and in the banks yesterday, today and tomorrow, modeling the war while fighting it. But clarity was now precious and just as hard in the fog of war. This changed the character of stress tests as defined in the regulations to a real world modeling exercise with real data and lots more of it to be urgently computed than any theoretical abstract ideas hitherto had offered banks to work with. Banks, however, found themselves more lost than ever about where they were and to start and how to do such sophisticated intellectually demanding and at the same time dangerous work. While before capital reserve ratios were at risk now the banks saw stress tests as threatening to their independence and solvency! To make matters worse the banks were now being told in no uncertain terms by governments, using a force majeure that the central banks and regulators had not dreamed before the crisis they could muster, to do stress tests pronto beginning with the top banks in the USA and where the stress tests in the Spring of 2009 were not about years hence but about their economic capital over the next 6 months!

They still did not employ their economists, leaving such corporately sensitives matter toa few trusted risk experts and accountants who are generally hopeless at economic models. Why, because economics is about dynamic changes over time, over months, quarters and years, and not about point in time cut-off audit figures for tax purposes; a wholly different game, a different language and culture. The USA results were eventually published but months later, only once the world had moved on.

Europe followed suit for its top banks and decided to keep the results secret. The reason for all this secrecy was less to do with corporate confidentiality or fear of the Jacobin mob and more to do with fear of real economists calling the whole exercise amateur, lies or even a sick joke. Economists weren't that interested, however; banking has always been somewhat beneath them. Traditionally finance was considered by economists to be immaterial to how economies behave - they have been learning a new hard lesson about that, but the lessons haven't yet sunk in and I suppose many economists are reluctant to acknowledge what they dangerously overlooked for so long. Sensible academics know better than to get involved in institutional mess of others just as the best bankers knew to steer clear of risk because there are no bonuses in risk management.

Now in 2010 all these stress tests are to be done again and banks have to consider the impact of an imminent recession and to think of it as double dip. banks hate this because it goes against their entire approach to Basel II, having believed it should be a way of reducing their capital requirements when it is obvious to all that the stress test results merely give regulators the perfect excuse to raise capital ratios to two or even three times what banks currently hold. They wouldn't do that, but the ammo is there should they wish to, to turn the clock back on capital reserve ratios to those prevailing 50 or more years ago!

In Europe, because of the sovereign debt crisis that has shifted the targets of capital markets short term speculators from attacking individuals banks to attacking all of national banking sectors, governments are fearful about the stress tests too and anxious that they should put their own banks in a competitively (defensive) good light. Even the very intelligent and feisty Christine Lagarde is anxious to use the tests as a good PR. That is of course the exact opposite of what the stress tests are for; they are for measuring worst-case not for showing relative better case.

In the case of France there is considerable suspicion that french banks have got away (with only a few exceptions) almost scot-free in their balance sheets, which look as though there had been almost no credit crunch or recession. German banks have not been so lucky and have had to evidence more financial embarassment than french banks. Belgian and Dutch banks were holed sunk (Fortis, ASBN-AMRO and Dexia) while ING and Rabobank were only holed above the waterline and continue to sail merely minus a few of their mainsails.

The results of bank stress tests will show that the eurozone’s financial services industry is in good health, France's finance minister Christine Lagarde has stated, thinking of course first and foremost about the reputation of France and her banks in the sovereign debt crisis. She made the comments at a conference as she announced that the test results will be unveiled on July 23rd. Financial regulators and watchdogs have been running the tests to quell investor concerns over the stability of the banking sector within the territory. But this is not what they are for! Banks are also worried now that they may be facing additional pressures from special taxes, regulation and stricter rules surrounding capital requirements, which they are already trying to postpone, the so-called Basel III requirements for higher economic capital buffers and liquidity reserves and for contributions to stabilisation funds. Ms Lagarde said: “

You will soon be seeing the number of banks that will be submitted to the stress test, you will have better understanding of the exact criteria we apply and of how heavily we stress the system.”

There is a French phrase "un coup de Trafalgar" which one might be forgiven for thinking it relates to be defeated. The phrase is certainly in the minds of the French, but "Non, pas de tout!" Un coup de Trafalgar translates as “an underhand trick.” You’ve got to love and admire the French who can turn defeat into a sneer, and there is something of this in how all countries and banks are actually managing their stress tests on a national banking sector basis as an arena for trickery to show things are better than expects, understandable perhaps in the presence of a submarine wolf pack of hedge fund capital market speculators who are hoping to profit from break-up and defeat of the Euro system, a defensive line of ships that are being broken apart just like at Trafalgar.

“Banks in Europe are solid and healthy,” Lagarde added.

The stress tests are expected to include approximately 100 of the largest banks in the Euro Area plus regional and local banks that are government owned. nationalised banks strictly do not have to comply with Basel II risk regulations but governments are concerned about how much their guarantees may be called upon and the embarassment this could means for budget deficits and national debts, given the parsimony of the ECB and the limits of the new €720bn stabilisation fund in the exclusive hands of the European Commission whose banking and accounting skills are not legendary. €720bn is five times one year's annual Commission budget. Has it got the what it takes to manage this responsibly or technically - non, pas dout!

In the UK, the FSA claimed that it is not worried over what will be revealed about the health of UK banks by the tests. Is this also flag-waving? Adair Turner, chairman of the FSA, was quoted by the WSJ saying rigorous domestic analysis on British financial institutions has been ongoing since the start of 2009. Of course, except that it is still more a matter of great seamanship more than great technical means. The pan-European stress tests are overseen by the European Union’s Cebs as supervisor of supervisors. The tests are said to be bigger, potentially more credible – and certainly longer winded. But, from the point of view of the banks there is still not explicit miodel and formulae that they can follow precisely. They are still being relied upon to innovate their own models and that for banks is a huge challenge. At best it will be 2 or 3 years before this work can be called professionally credible, possibly not even then?

According to people involved in the European testing process, the initial exercise of testing the biggest banks in each country – 26 institutions had been done and is on schedule for publication on July 15. July 14 would have been a more resonant date. In my view if the tests and results are available by then, then the process has been far too rushed and the chances of credible results even less probably, certainly no time for boards to approve them and no time for any interative reworking to improve on the initial fag packet models.

CEBS questionnaires will have to be sent out via national banking regulators to about 125 institutions. The big question is whether the process will work in its aim to restore battered confidence in European banks. To repeat myself, if this is the aim it is wrongheaded according to the regulatory laws and the experts know that. European banks are worth 10 per cent less on average than two months ago, according to the FTSE Eurofirst 300 banks index. Enlarging the test should mean it takes to the end of July. I'd have specified end of September, but who wants to be worrying about all this while on their August holiday breaks.

Spain in particular is desperate to restore confidence in its banks quickly. Spain, which has tested all its banks according to CEBS guidelines is desperate to publish the results, has been instrumental in strong-arming other countries into extending the remit of the test, according to several people involved in the process. But, since this has become a competitive sovereign debt battle all have to publish, to fire their guns, at the same time. Germany was persuaded that to limit its test to only its three biggest banks was self-defeating, implicitly damning other untested institutions, notably the state-owned Landesbanken. The FT and others have commented that it is far from clear that the parameters of the tests will be tough enough to restore confidence across Europe. The same was said in 2009, and actually the CEBS tests are broadly a repeat of the exercise carried out in 2009, the quality of which I know to have been work that I would not pass if brought to me by first year undergraduates in either economic or business management school.

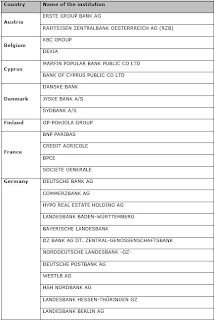

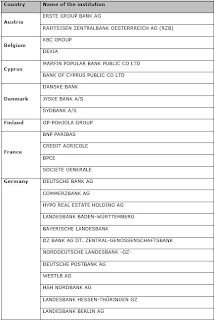

The banks to be stress-tested are:

The parameters would be broadly a 3% GDP (in real inflation adjusted terms, which are useless for banks) undershoot, a 1% increase in unemployment and 10% further fall in property prices. Where is the figure for fall in corporate profits or spike in interbank borrowing rates, sovereign debt ratings and business profits wholly absorbed by debt servicing, insolvency rates and other such data - banks have to make those up.

Adding to parameters widely seen as credible, CEBS is poised to settle on a higher hurdle rate for passing the test, increasing the number from a 4 per cent tier one ratio in last year’s test to 6 per cent this time, in line with the US stress test last year which helped restore confidence in banks there. This in itself is simplistically not the whole picture. The total capital reserves of all types and qualities should be included, including all capital buffers and other liquid and near-liquid reserves, including over the medium term between nominal losses to realised losses and collateral receovery and selling off business units. Net interest income is critical and this has to be modelled over a cycle, not based on point in time calculations. the results of all the stress tests will be predominantly point in time calculations.

A key part in the exercise is how the tests choose to measure the sovereign debt risk impacts on the banks on both sides of the balance sheet. One regulator said to the FT that Europe had decided the test should assume a “haircut” of about 3 per cent on all eurozone sovereign debt investments. This is significant for otherwise highly rated instruments, but foolish as a general rule for all. 25% haircuts operate on asset swaps and 20% on debt restructurings such as Greece. That 3%, which is less than the haircut on most collateral receovery costs as already imputted in Basel II, will be controversial because it would discount solid German Bunds at the same rate as troubled Greek government debt. In that regard it is at least right because inflation alone could have that much impact, but of course how inflation is treated from real GDP to actual bank cash flows is a messy business.

“Given the difficulties, the preferable solution would be for each bank to disclose exposures so investors can base decisions on the facts, rather than questioning an imperfect test,” said Huw van Steenis to the FT, an analyst at Morgan Stanley. However, one senior official told the FT that the alternative idea of disclosing each bank’s sovereign holdings would be implemented as well. Combined with the running of simultaneous testing on a “top-down” basis by European authorities of the systemic macro-economic solidity of various banking sector exposures, such as commercial property, there is a growing belief that these stress tests could reassure the market sufficiently, as planned, is the FT's conclusion, adding that some analysts have suggested that panic about European banks’ exposure to sovereign debt could be overheated. All experts, including myself, agtree it is appallingly overheated and overheated by politicians as much as by speculators and runour-mongers and bloggers, but that the tests results will be reassuring I and other very much doubt, because the quality is easily comparable to the reassurances banks issued in 2008 saying they have no funding problems. The actual fact is that banbks do not know what their funding problems actually are because the uinterbank funding markets ahave been relatively closed in recent months and these tests are part of the battle, treated as a weapon not merely the half-time scorecard.

Moody’s, the discredited, and in Europe deeply despised including openly by the ECB, credit rating agency, last month concluded that the largest lenders would be able to absorb “severe” losses on their exposure to Greek, Portuguese, Spanish and Irish assets without having to raise additional capital, after carrying out its own stress tests on more than 30 European banks. I believe them. It does not take much analysis at all to know that much. Moody's test assumed a forced sale of public sector bonds at 20 per cent below the steepest fall in market valuation in recent months, an event Moody’s described as very low probability.

The credibility of CEBS’s latest tests will hinge on whether enough weaker banks fail, said one senior central banker in London this week, reported by the FT. “The tests need to be published, the parameters need to be fully transparent, and some banks need to fail.” That is in my opinion silly and irresponsible because as anyone must know the authorities will intervene before absolute failure, and in any case we don't have perfect agreed measures for what counts as failure.

There are more competing theories for how to measure a banmk's insolvency than there are stress test factors and scenarios. Several industry groups, such as the British Banking Association, have come out against bank-by-bank disclosure, saying that league-table-like results could trigger a panic run on an otherwise healthy institutions. However, many bank chief executives and chief financial officers concede that full disclosure might be the only way to address investors’ concerns, according to the FT.

What all seem to miss is that this is in the sopvereign debt context now and therefore the stress tests are of national banking sectors, not about individual banks. This is macro-prudential systemic risk stuff not microprudential. Anyone liuving in the let some fail so others can survive better totally misunderstands the interdependencies of banks and of banks and economies. Christine Lagarde understands that. What the tests will again prove is that bankers don't understand the economics of banking, least of all investment bankers, no true perspective or realistic sense of proportion. Unfortunately our economies are in the hands of banmks as much as the banks are in the hands of the economies where they do business but neither lendfers nor customer want to acknowledge their vulnerability to the other. Governments and central banks understand what matters most in this crisis but they are being attacked and weakened by the buccaneers and privateers of the capital markets!

Recent articles in the UK press have noted how asset securitisations (ABS)including those based on mortgage debt (underling loan assets)have held up well in terms of yields despite the fall since 2007 in their market prices. The suggestion is that banks need to refinance and issuing new securitisations are the obvious solution (selling to ivestors instead of heavily discounted by 'haircuts' to central banks). The problem this solution faces is how to restore market confidence in this asset class. It can only be done by better information - more transparancy - on reliability of the yields (investment income returns) in the hope that confidence in capital values will follow?

Recent articles in the UK press have noted how asset securitisations (ABS)including those based on mortgage debt (underling loan assets)have held up well in terms of yields despite the fall since 2007 in their market prices. The suggestion is that banks need to refinance and issuing new securitisations are the obvious solution (selling to ivestors instead of heavily discounted by 'haircuts' to central banks). The problem this solution faces is how to restore market confidence in this asset class. It can only be done by better information - more transparancy - on reliability of the yields (investment income returns) in the hope that confidence in capital values will follow? Many major banks would have saved themselves many times those costs had they accepted borrowing at the higher wholesale rates but could not break from their past business model margins, especially those whose refinancing was an aggressively large portion of their balance sheet. Banks who had to refinance funding gaps (gap between deposits and loans) in the ehat of the Credit Crunch were nailed to a cross and looked potentially insolvent. They were lambs to the slaughter for the shorting speculators. Arguably there was no speculation involved for about 18 minths because shorting these bank stocks was a sure-fired profit winner egregiously helped by irresponsible stock lenders.

Many major banks would have saved themselves many times those costs had they accepted borrowing at the higher wholesale rates but could not break from their past business model margins, especially those whose refinancing was an aggressively large portion of their balance sheet. Banks who had to refinance funding gaps (gap between deposits and loans) in the ehat of the Credit Crunch were nailed to a cross and looked potentially insolvent. They were lambs to the slaughter for the shorting speculators. Arguably there was no speculation involved for about 18 minths because shorting these bank stocks was a sure-fired profit winner egregiously helped by irresponsible stock lenders.